This past October Kelly Storie and Mélanie Broguet attended the Salon du Chocolat de Paris (the Paris Chocolate Salon), which took place from October 28th to November 1st at the Paris Expo Porte de Versailles pavilion—a first for Camino!

We were amazed by the sheer scale of the event from the moment we arrived. It boasted 500 exhibitors from over 30 countries spread across 200,000 square feet divided in two levels. This flagship event in Paris gathers 100,000 chocolate lovers every year.

The Salon really puts CHOCOLATE on a pedestal. It showcases both the refined, luxurious side of chocolate, with all of its pastes and flakes, as well as its raw properties which highlight the cacao bean’s unique origins.

On the Salon’s first level, we found gourmet chocolate in every shape and size. Among the displays, each one as sumptuous as the last, chocolate was presented like jewellery in a gift box, in a myriad of forms: bars, candies, jewellery, truffles, cakes, etc.

On this level were the chocolate vendors, artisans, popular chocolate brands, chefs, culinary workshops, and even chocolate dress designers.

The second level gave visitors a chance to learn about the cacao bean’s terroir by teaching them about various countries of origin. The very soul of chocolate could be found among the bean-to-bar makers, cacao-producer associations and guest speakers who reminded conference-goers that everything starts with the vital work of cacao farmers.

We decided to start on the second level when we arrived at the Salon so we could take part in a mini-conference about bean-to-bar chocolate making delivered by French chocolate expert Chloé Doutre-Roussel. A bean-to-bar chocolate maker is one who produces small quantities of chocolate (fewer than 500 kg per batch) directly from the cacao bean. This small-scale technique transforms the beans to chocolate often using artisanal methods.

From Bean to Bar

The bean-to-bar movement is a reaction to the mass production of chocolate by multinationals, which often results in product that has a simple, one-dimensional flavour. The movement emerged a decade ago in North America and has since taken off. Bean-to-bar makers can now be found the world over, including in cacao-producing countries—a rarity ten years ago. Chocolate lovers are no longer simply seeking the highest percentage of cacao in their chocolate; their palates have become more sophisticated and they’re willing to spend a bit extra to explore the bean’s different qualities and flavour nuances. They’re also more aware of the origins of beans and want to be able to trace them. This taste evolution has encouraged countless small artisanal makers to produce bean-to-bar chocolate using modest methods that don’t rely on traditional chocolate-making equipment, which can be costly.

The bean-to-bar movement appears to be having a positive impact. Besides raising the overall quality of chocolate and diversifying its flavours, it has allowed artisans to connect directly with cacao producers, eliminating corporate middlemen such as buyers and processors. It has strengthened cacao-growing communities by encouraging them to improve the quality of their beans which are very specific to their terroir, and by selling directly to the artisanal maker. In the end, one could draw many parallels between the bean-to-bar movement and Camino’s mission.

Our Discoveries

We were able to sample chocolate bars whose distinct origins were explained by their bean-to-bar makers. Those cacao beans came from such places as Vietnam, Brazil and Nicaragua, just to name a few.

Cacao beans have very complex flavours. As with wine grapes, the taste of a cacao bean varies depending on its type, its country of origin, and its specific terroir, all of which allow makers to play with many possible combinations to create chocolate with a distinct character.

The Salon also delivered some surprising discoveries, like the Amma brand bar from Brazil, which is made from the cupuaçu bean (Theobroma grandiflorum). The cupuaçu is a tropical rainforest tree related to the Amazonian cacao tree (Theobroma cacao) and is heavily cultivated in Brazil’s north. While sampling Amma’s Theobroma Grandiflorum Cupuaçu, we noticed that its taste was very similar to that of chocolate. However, it had a pleasant smoother mouthfeel which can be explained by the fact that cupuaçu beans are made up of a greater quantity of certain types of fatty acids that melt more quickly than those found in cocoa beans.

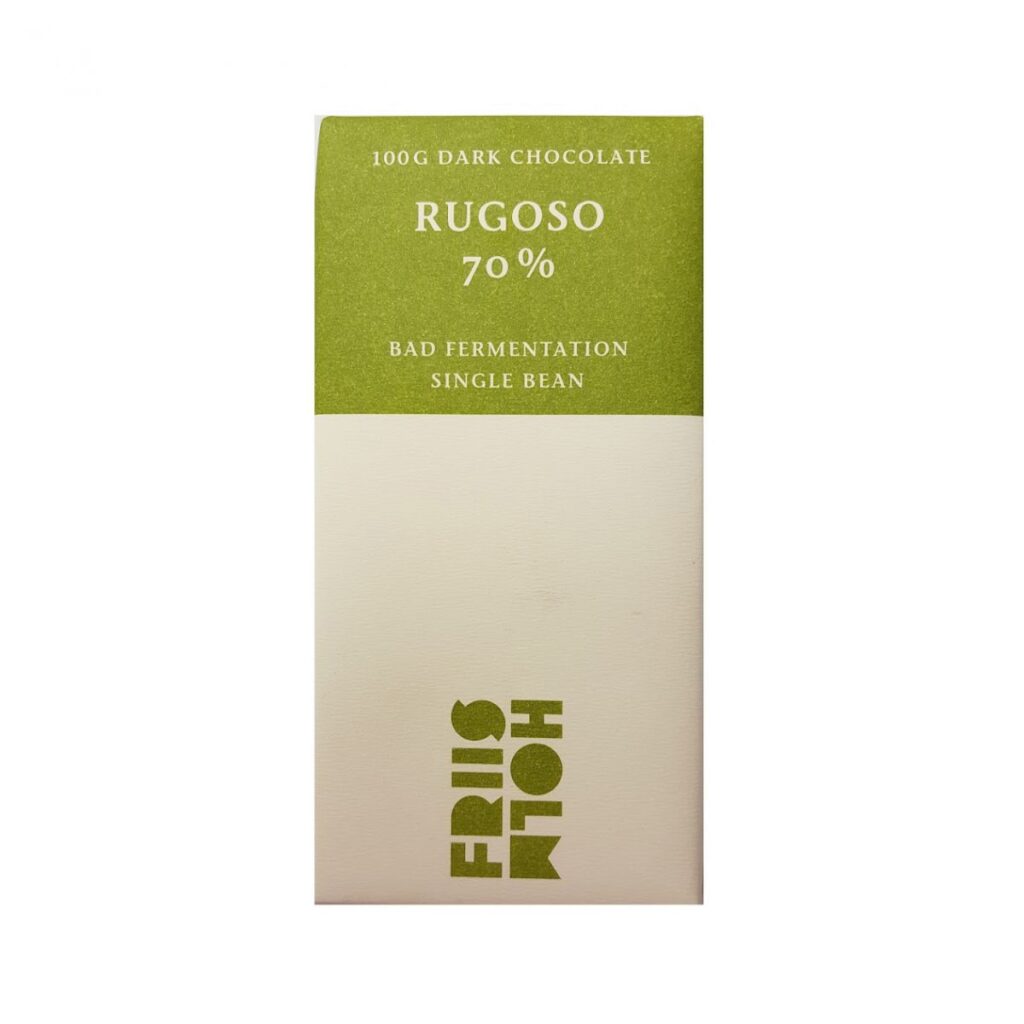

Another discovery came in the form of chocolate made from so-called “poorly fermented” cacao beans, which was created by Mikkel Friis Holm, a Danish chocolate maker who has won multiple International Chocolate Awards. He explained that, after one of his visits to Nicaragua, where he sources most of his cacao beans, he sampled beans that weren’t properly fermented according to industry standards. Conventional fermentation measures fermentation quality based on colour rather than taste, but when Holm tasted beans destined to be destroyed due to their lack of fermentation, he noted that they weren’t at all terrible and decided to see what would happen when he converted them into chocolate—and the results were remarkable. This bar, labelled “Rugoso 70% Bad Fermentation,” has since won a silver medal at the International Chocolate Awards, European division (semi-finals*)!

After a day at the Salon du Chocolate de Paris, where we met with various industry players, explored the booths in search of new trends, and obviously sampled a lot of chocolate, we left brimming with inspiration.

In closing, here’s the short promotional video about the Salon:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAeRbjIeDsc&feature=youtu.be

*The final takes places at the international level